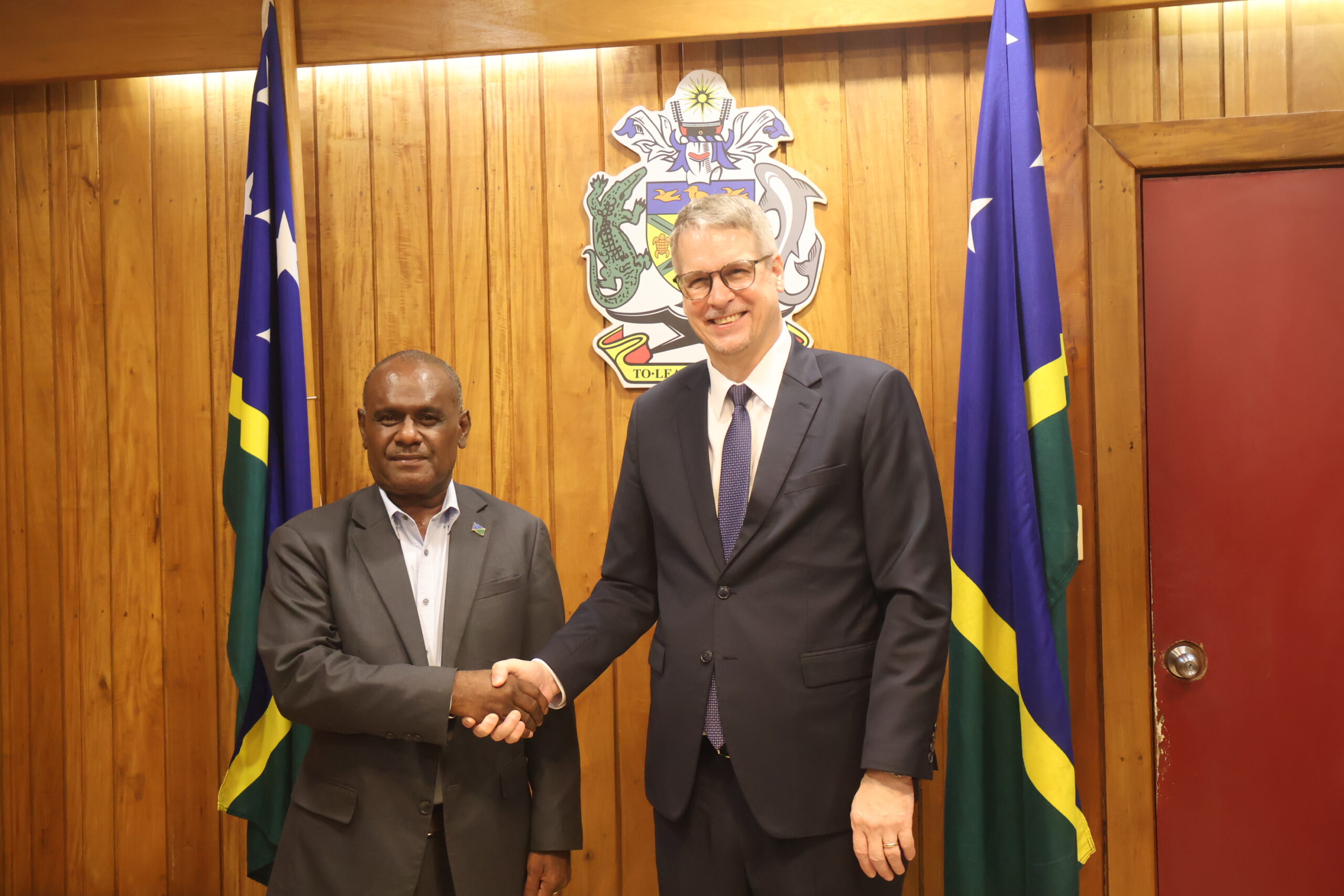

A meeting between Solomon Islands’ new Prime Minister Jeremiah Manele and Australian Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles in Honiara on May 21 suggested a change in leadership may have given the two governments an opportunity to renew their relationship. Bilateral relations suffered during the tenure of Manale’s predecessor Manasseh Sogavare, a regular critic of Australia whose decision in early 2022 to strike a comprehensive security deal with China raised concerns in Canberra.

Manele, who co-signed the security pact as Sogovare’s foreign minister, is known to share his predecessor’s pro-Beijing leanings. But the newly elected leader, who previously worked with Australian officials involved in the Regional Assistance Mission in the Solomon Islands (RAMSI), is widely seen by Australian insiders and analysts as a less combative figure and someone Canberra can work with.

On that front, Marles’ trip to the Solomon Islands appears to show that Canberra’s relationship with the new administration is on track, with Manele confirming the “depth and strength” of the bilateral relationship and telling Marles that “I want to see our relationship continue during my time in office to rise to new heights.”

Front and center in efforts to restore ties are likely to be in the areas of security cooperation, development aid and budget assistance – each discussed during the visit. The former in particular has been the focus of considerable attention since the China-Solomon Islands security pact, with Marles stressing that the decision to visit Honiara so soon after the election of a new prime minister was prompted by Canberra’s commitment to “being Solomon Islands go to security partner.”

But raising the bar on Australia’s aid efforts is unlikely to be any less crucial to cementing ties. During Marles’ visit, Manale said he was particularly interested in “fast-tracking” projects with partners that would “help Solomon Islands move forward faster to achieve its economic, social and security goals”. He also said that “budgetary support” would help “further strengthen our relationship”.

On that front, there can be no doubting the generosity of Australia’s aid packages to date – a fact acknowledged by Manele. Since RAMSI was withdrawn in 2017, Australia has provided more than AU$800 million in assistance in key areas including security, health, education, agriculture and governance.

The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) 2022–2023 report ranked the performance of Australia’s development program in the Solomon Islands as only “adequate” in terms of effectiveness in most categories, including health and education. None of them achieved a “very good” rating. The final investment monitoring report for Solomon Islands’ 2023 governance program gave it a “less than adequate” rating.

Yet these modest assessments probably outweigh what some consider a visceral assessment of the performance of Australia’s aid programs. Of course, Australia is not fully responsible for outcomes that depend on governance and policy decisions in another sovereign state. But the cold reality is that despite decades of multibillion-dollar aid, the Solomon Islands remains one of the most poverty-stricken nations in the most aid-dependent region of the planet. This is confirmed not only by anecdotal observations, but also by statistics, with Solomon Islands’ GDP per capita significantly lower than Papua New Guinea’s, less than half of Tonga’s and Samoa’s, and slightly more than a third of Tuvalu’s. and Fiji.

All this bolstered former PM Sogavare, who has long insisted that Australian aid is fueling dependency, not moving the nation towards economic self-determination. This judgment was reflected in his signature “look north” campaign policy, which advocated reducing dependence on Australian aid by expanding trade and investment ties with China. His party’s significant loss of seats in the last election, though undoubtedly the result of a number of factors and not just foreign policy, means that the wider popularity of this view is questionable. However, Canberra should be concerned that this has now become a recurring theme in the Melanesian sphere.

The “Look North” policy is actually the namesake of a series of policies adopted over the past few decades in Melanesia, the first being that adopted by Papua New Guinea (PNG) in the early 1990s. This came as PNG’s economy and relationship with the Paul Keating-led Australian government suffered concurrent crises. PNG’s then leader, Paias Wingti, appeared to feel Australia was “holding PNG back economically”, according to a DFAT official at the time – perhaps an accusation that Canberra was fueling aid dependency. He was also apparently “happy to see the weakening of Australian influence, particularly in the economy”.

In the next decade, another government whose relationship with Australia was in crisis adopted a “look north” policy: Fiji. It comes after the Australian government took a hard line in response to the coup that overthrew Fiji’s government in late 2006, including curbs on state aid and security cooperation. Still, according to some experts, Fiji’s new policy was underpinned by a broader aspiration to penetrate global markets to expand national agency and economic determination. This intersected with China’s push into the Pacific through the Belt and Road Initiative and was a precursor to Fiji’s entry into closer and extended security cooperation with China.

Of course, Canberra would counter by claiming that it is deliberately holding back the nations of the region – or under its control – through its aid regime. However, underlying this recurring perception problem among Melanesian elites is that while individual programs have brought untold benefits to local communities, the overall picture of Australian aid in the Pacific is not flattering.

The reality is that the Melanesian sphere, which with few exceptions has been the main focus of Australia’s Pacific aid, is generally poorer per capita than its Polynesian and Micronesian counterparts – which are more influenced by New Zealand and the United States. states, respectively, with the sole exception of Fiji. Mountains of health aid have also failed to prevent a substantial widening of the gap between life expectancy in Pacific island countries and the global average. In addition, several recipient countries of Australian aid in the Melanesian sphere and beyond have some of the worst infant mortality rates outside of Africa.

Each of these questions is very important in its own right. Yet they may also have played a key role in past failures in an area of primary concern to Canberra: regional stability. Infant mortality, GDP per capita and life expectancy have been identified by researchers as predictors of political instability.

Given this, it is notable that when Papua New Guinea, Fiji, and the Solomon Islands independently adopted a “look north” policy or entered into comprehensive security agreements with China, it was in each case only a few years after major social and political unrest. In PNG, “look north” emerged during the ongoing conflict in Bougainville and amid years of growing instability and lawlessness following a painful economic transition from an agrarian to a resource-based capitalist economy. In the case of Fiji, it was adopted after the latest in a series of coups. And in the Solomon Islands, a security agreement with China came after years of internal disputes, suppressed with some success by the Australian-led RAMSI, but re-emerged after Honiara agreed to shift diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to the People’s Republic of China.

Poor performance on economic and health predictors of social instability also appears to correlate with decisions by Pacific Island countries to move closer to Beijing. When the Solomon Islands and Kiribati switched diplomatic loyalties from Taipei to Beijing, both Pacific island nations fell to the bottom of the region’s league table in terms of GDP per capita. Kiribati, along with Papua New Guinea, also performed poorly in a global comparison of life expectancy, and both nations, along with East Timor, have the highest infant mortality rates in the region. East Timor and Papua New Guinea are also among the poorest countries in the region on a per capita basis.

The latter two in particular have also recently moved towards China’s security. East Timor, which Singapore’s foreign minister last year said was a “practically failing state”, its Prime Minister Xanana Gusmao agreed last year to sign a joint pact between China and East Timor that upgraded the two nations’ relationship to a “comprehensive strategic partnership” and enhanced military cooperation . Soon after, East Timor President José Ramos-Horta revealed that he had taken the initiative to ask Beijing for help in developing police and military infrastructure.

It emerged earlier this month that Australian diplomats were trying to avert a police deal between China and Papua New Guinea, months after widespread unrest broke out in PNG’s capital Port Moresby.

Given that the main focus of Australia’s regional aid diplomacy is to deny China a security foothold in the region, these factors likely support a different view of what should be the priorities of Canberra’s assistance programs. Rather than investing in aid to influence the foreign policies of nations that have clearly emphasized their own agency in recent times, perhaps Australian aid should focus primarily on the causes of instability that might lead Pacific Island countries to trade their sovereignty for security. In other words, Australia should seek to study and identify the factors, such as those mentioned above, that make the Pacific Islands unstable, and design a results-oriented approach that prioritizes improvement in these areas.

There are practical reasons for this. The first is that although Canberra is extracting some diplomatic capital by “out-bidding” China on the aid front, this is not a winning strategy in the long run. Unless Australia gets investment in the region from stronger allies, most of whom have less strategic visibility in the game, economic asymmetries mean Canberra has little chance of defeating Beijing’s proxy diplomacy should Beijing pull all the stops to increase its influence. .

And while Canberra is also currently winning in experience and capability on the aid front, Beijing is looking for ways to up its game, particularly in health diplomacy, where it supports research and builds smaller programs such as earlier engagements between the Solomon Islands Health Officials and the Medical Guizhou University. Again, resource and personnel asymmetries make Australia’s long-term prospects outside of rival China a risky bet on this front.

Second, while adaptability and responsiveness are always essential virtues in development aid planning, designing aid programs around a sharper organizational concept could make programs more focused, coherent, and focused on tangible results-based metrics.

But last and most importantly, with a focus on enhancing stability and expanding the agency of Pacific Island Nations, such a strategy is likely to better align the goals and interests of Australian and Pacific Island leaders. This, in turn, will pave the way for less skepticism and closer engagement to achieve outcomes that serve both Pacific Island nations and Canberra’s collective security interests. Building trust in this way can also strengthen Australia’s aspirations to remain a “security partner of choice”.

Such an approach may encounter resistance in Canberra, which is still determined to “win” its “strategic competition” with Beijing in the region through its policy of a stronger Pacific family. Yet there is little sign that this is an agenda the Pacific island nation is passionate about. Better targeting of aid to help Pacific island nations feel more secure about their future, by investing in mitigating the potential causes of crises, rather than simply strengthening capacities to respond to them, could better position these countries to resist intrusive security arrangements that could threaten their sovereignty and jeopardize Australia’s security interests.

This means investing trust in premium Pacific island nations that, with no existential security concerns, maintain the “friends to all” policies they see as key to maximizing their agency. If the history of the “look north” policy is anything to go by, it is at least better to be seen as an enabler than a perceived obstacle.